On Keeping a Family Archive

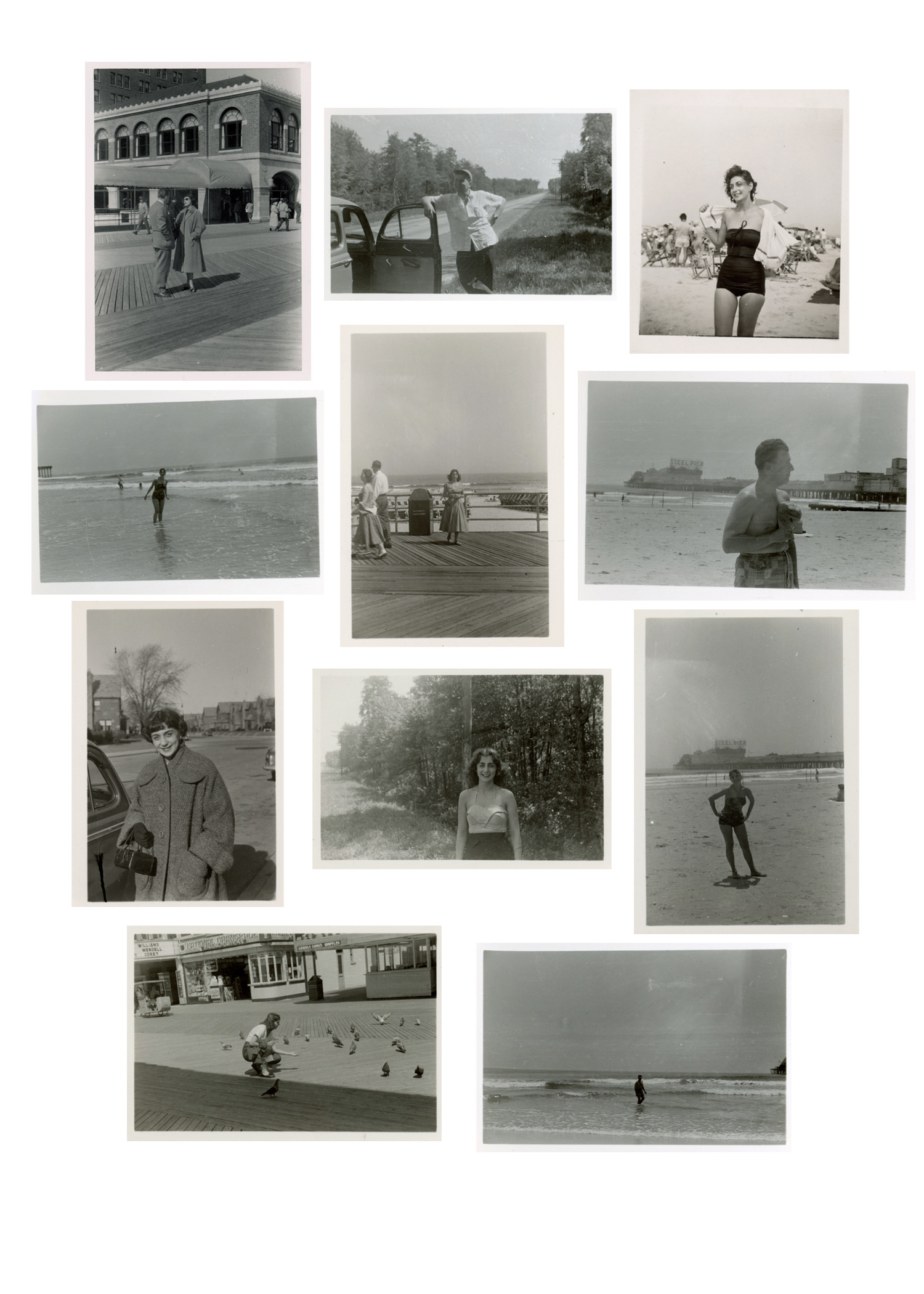

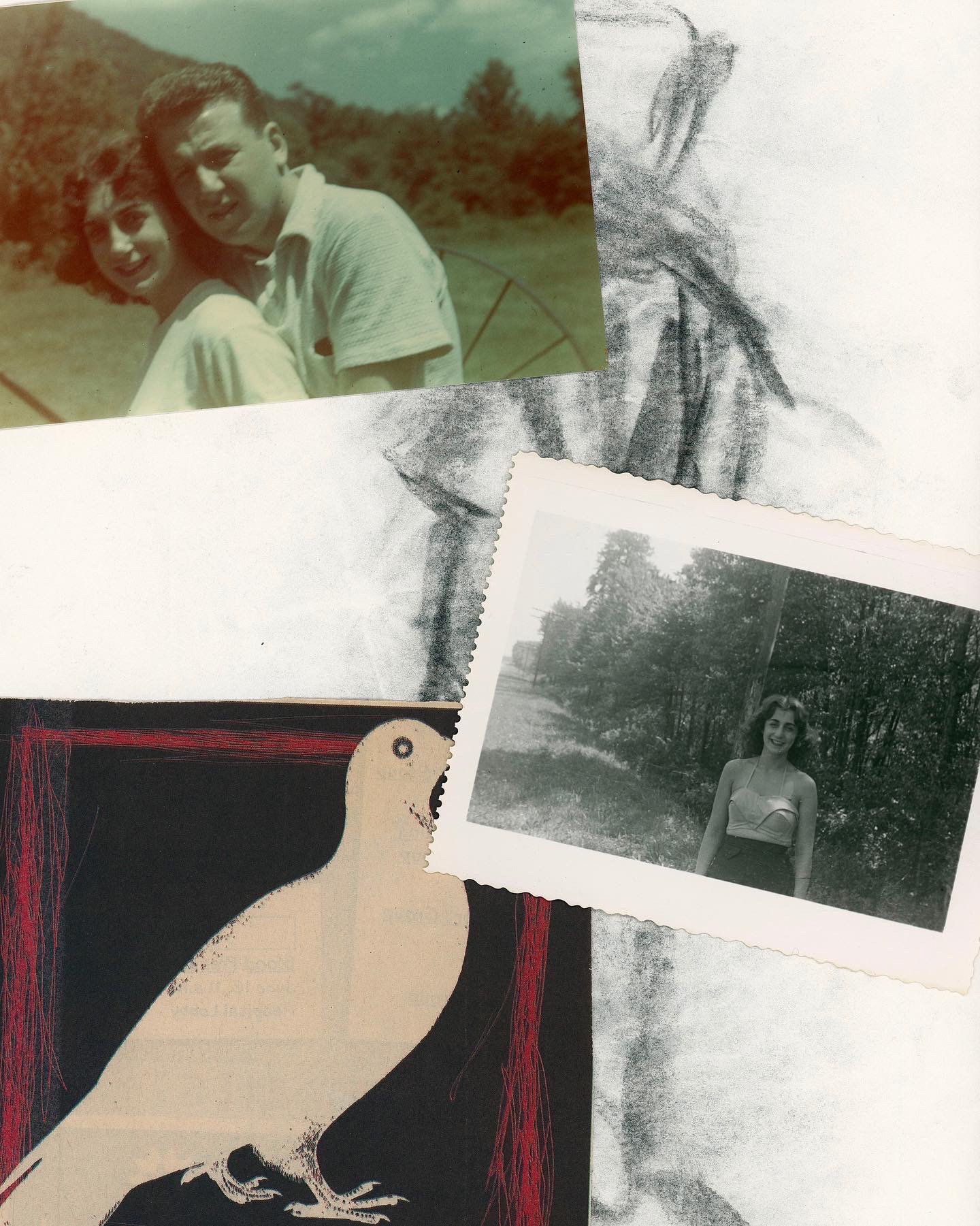

I have always found this special richness within my family, specifically my father’s side. It is rooted in my grandparents calling the house phone before they made their way over for dinner, the glass coffee cups they always used, or the candy dish that rested atop a glass table littered tastefully with their travel tchotchkes. That special richness stemmed once I began to discover photographs. It began with the images of my grandmother with her dark lips and curled bangs, before she had my father and his brother, or my grandfather with his mouth open on a street corner. Then it stemmed farther once I began to see my own reflection in the images of those who came before me. It grew into recognizing the love that became who I am, as a descendent and as an artist. I grow older and there is more loving comparison between Arline and me, more over the fact that I have her nose and her forehead and her hair. I am told she would have worn the sweaters I wear, that she did the same thing I did when she went to museums and collected images through the camera. I grow older and make eye contact with the same striking eyes of my grandfather as he looked at me as a child when I discover photographs of him and Mel Brooks together during the war. These experiences I’ve had since both have passed have been almost melancholic, they cause a lump in my throat, but they are also, in a way, encouraging. They are encouraging as I truly do recognize the love that came before me, but more so, the life that came before me.

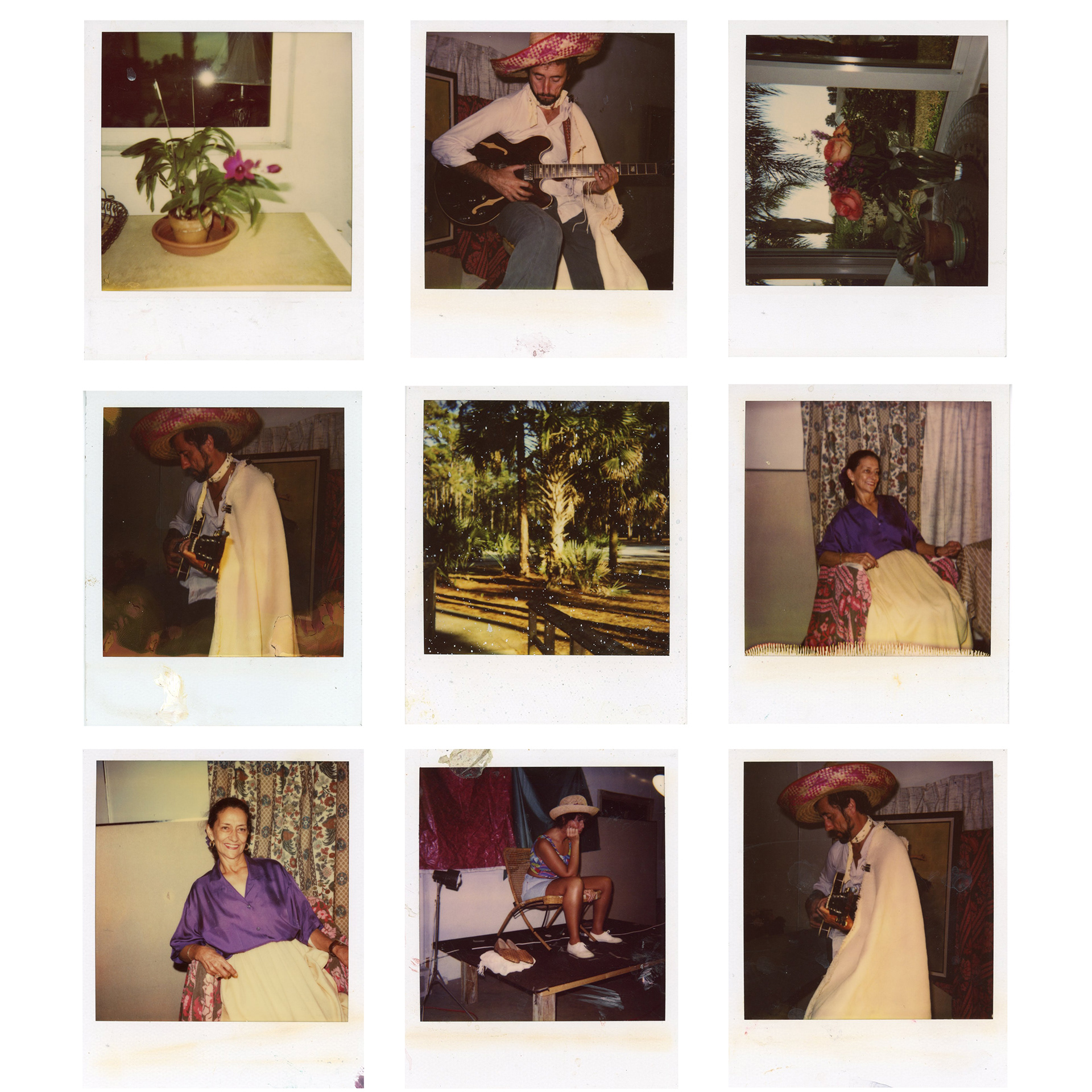

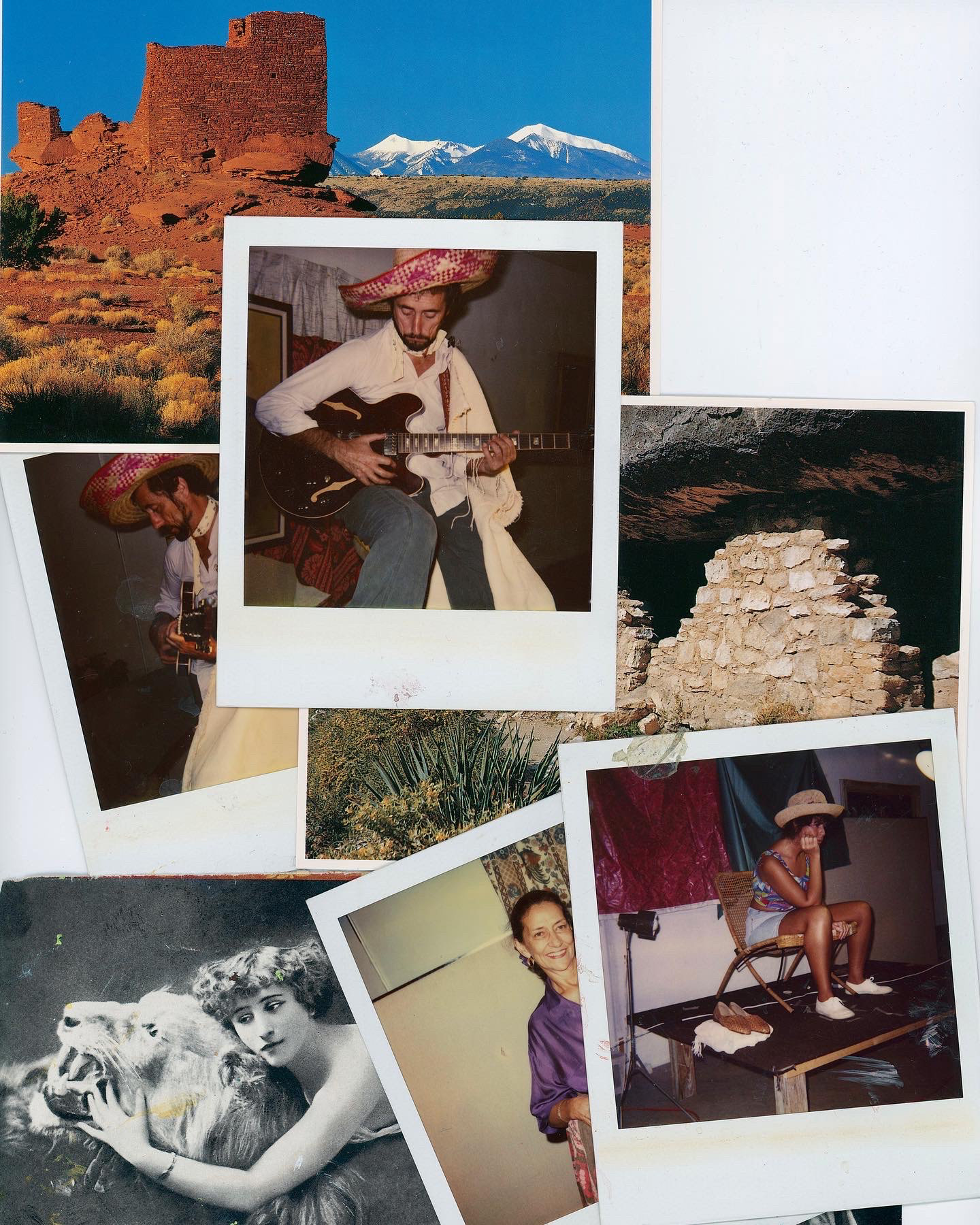

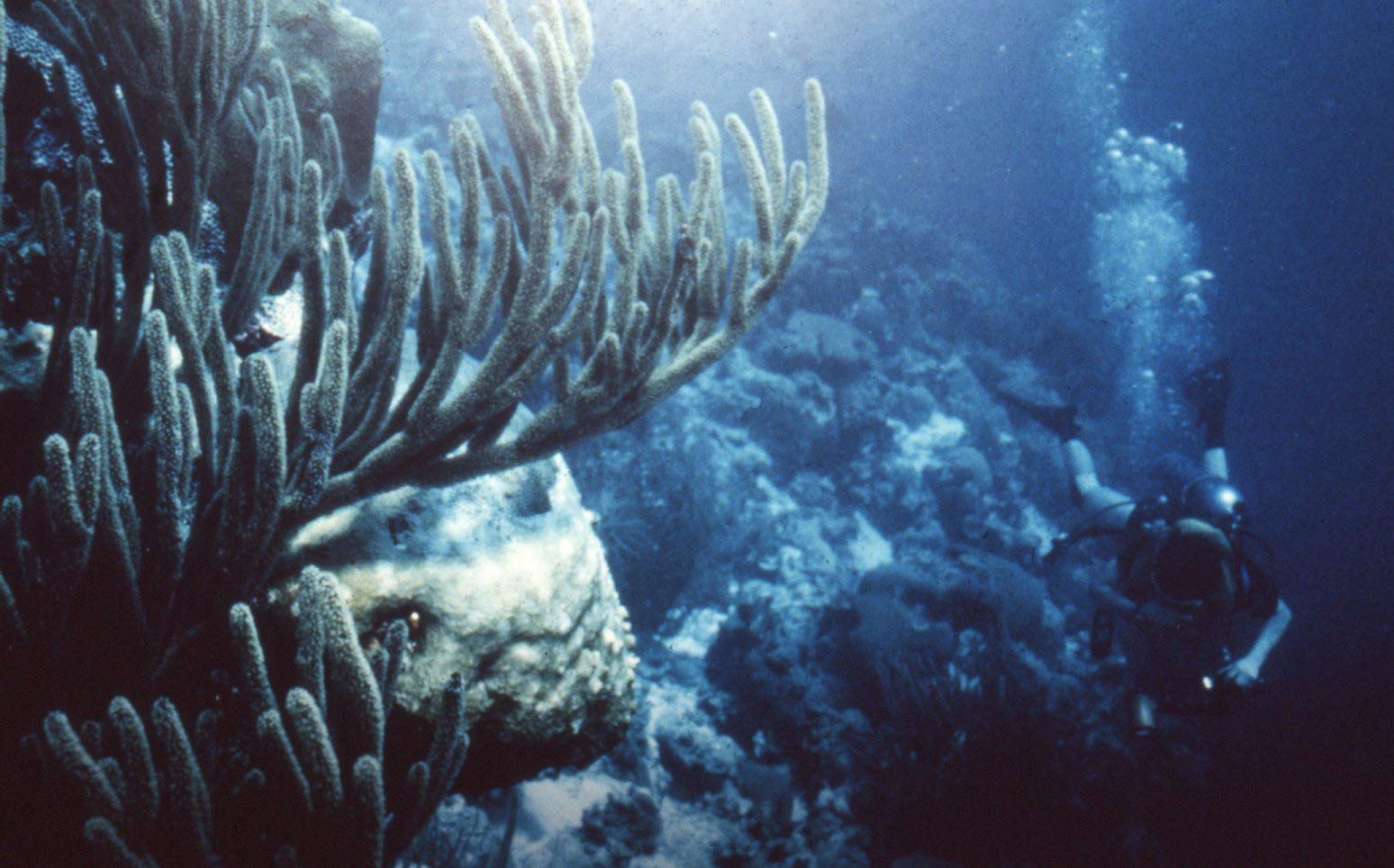

Like a tree, the discovery of photographs from my grandparents branched off into a dive of my father’s photography. My father grew up in the suburbs across Long Island, New York. He spent his late twenties and thirties scuba diving with his friends in the tropics of the Florida Keys and Bonaire and camping in the creeks of Upstate New York. The bedtime stories of Alexander Salamander and his brother Sam came to life with the discovery of boxes upon boxes of Ektachrome and Kodacolor slide film. Those stories were about him; the stories of brushing against fire coral and experiencing a flaming touch, a starry night over Havana Glen with nothing to be heard but a fire crackling, or a cycling expedition with an Italian lad out of a tall tale all came to life within the thirty-five millimeter frames of positive images. The silos of his university or the breakfast place in Newport, Rhode Island, in which I have visited on family trips, are still there, and they remain etched by light and through the individual eyes of my father.

Ben and I began a birthday gift to my father by first flipping through a few slides I had in a cigar box, then eventually he gave us a few boxes and said, “have at it.” Opening the boxes emitted a specific, positive energy in my room, I can’t say what it was, but it was like getting your own developed film back. We spent a couple of hours sifting out negatives by simply holding them up to the light and using our intuition. “Put that in the scan pile”, “Wow, do you see those colors?”, “Ben, look, he is wearing a Chai around his neck.” We ended up scanning over fifty images from at least ten rolls of film, like time capsules and dreamscapes. My father was elated to see what we have been up to. I told him he could make some big bucks from his photographs, especially the ones he shot using a (his and now mine, our, I suppose) Minolta XD-11 in an underwater housing. He was flattered, agreed with the compliment, but I said that with the intention of not reaping materialistic reward, but of expressing how warm and fulfilling doing all of this was, in Steven language, perhaps.

As I write, I realize I am using a past tense, like when talking about my grandparents. Keeping a family archive allows one to not only preserve a family legacy, but to create a sense of presence. There is also a sense of presence created within oneself that I have found while filtering through images (and having conversations with my father about where a picture was taken and who was in it and if he remembered what he ate for dinner that day). It has been a meditative endeavor, like most of my artmaking is. In looking through the photographs of people who I am biologically related to and deem myself to know and have known very well, I am looking at people who do not know me at all and people who are living their own lives before deciding to become fathers and mothers. I am solely a viewer, relaxing and exciting me all at once. Within the grounded atmosphere this activity brings, it also brings a sense of gratitude. On what I stated earlier, I feel encouraged. I do not long to be part of the days that are illustrated in these photographs, but rather I long to continue them by preservation, thus I am encouraged to continue in my own creation of images.